20 Best Foreign-Language Movies on Max (HBO Max)

Don’t let subtitles, unfamiliar storylines, and minor differences in acting styles close you off from discovering the many worlds of non-English language cinema. Once you get over that one-inch-tall barrier (as Parasite director Bong Joon-ho said), it’ll be easy to discover that “foreign” movies already offer so much of what you enjoy from the films you’re used to. And on Max—the streaming service of the network known for its prestige content—the non-English language films available to you possess that same prestige as well. These are titles you may not be very familiar with, but through great storytelling and excellent craft they prove that international cinema isn’t just something to be dismissed as pretentious or weird; these films push the rest of the global industry to be better.

Jump to the top 10:

When the film publication Sight and Sound dubbed it “the greatest film of all time,” movie fans were quick to give their opinion. Those opposed complained about its simplicity, while those favoring the film praised the same trait. It’s true the film is simple—the camera is static and far away, and all it does is follow the titular Jeanne as she goes through the strict routines of her life. But nothing about it is plain or easy. You could mine a thousand things from a single scene alone, to say nothing about the woman at the center of it all. As Jeanne juggles her duties as a homekeeper, mother, and breadwinner, she eventually unravels, and the film rewards us with one of the most memorable climaxes of all time. There’s complexity in the ordinary, Akerman reminds us in her mundane epic, and there’s always something political motivating our choices, no matter how normal they seem.

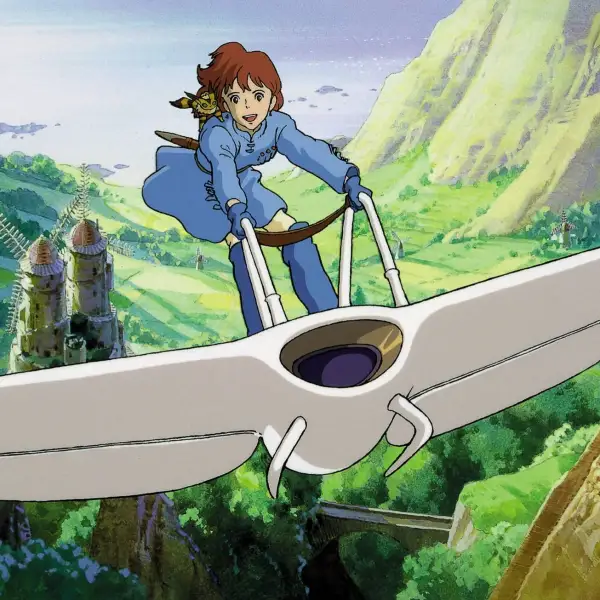

This post-apocalyptic sci-fi adventure might have escaped the radar of most Ghibli fans, but that’s mostly because it isn’t a Studio Ghibli film. Shocker, I know. But that’s the reason why Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind deserves more love. In its manga form, Nausicaä proved that Hayao Miyazaki was capable of the nuanced, yet epic storytelling that is rare to see in action comics. In its movie form, Nausicaä also proved that that storytelling can jump straight to the silver screen, and that Miyazaki works best with his own original work. In other words, Nausicaä was a Ghibli film before the studio was created, and its resulting success proved that audiences were hungry for more.

This unique romance is set during a time when a man would be sent the painting of the woman he was to marry before the wedding could take place. Héloïse, secluded with her mother and a maid on a remote island, doesn’t approve of her upcoming wedding and refuses to be painted. Her mother sends for a new painter, Marianne, to try to paint her without her noticing. Marianne has to take on this near-impossible task when she starts having feelings for Héloïse. This makes for a riveting romance where Marianne has to choose between her heart and her art while keeping a huge secret from her love interest.

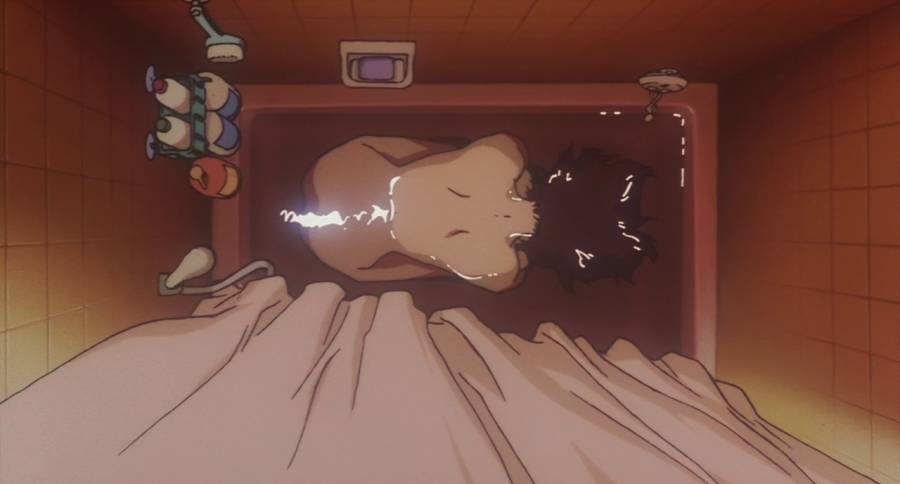

Satoshi Kon’s Perfect Blue is a chilling psychological thriller and a fantastic next step for those looking to explore anime’s dark side. Kon animates with Hitchcockian flair and is so successful at memorable compositions that Darren Aronofsky even lifted a scene from this into Requiem for a Dream.

Mima is a pop idol who abandons her singing career to become an actress. Shaken by a series of murders, and a stalker who knows her every move, she begins to lose her grip on reality. The rest is a riveting ride into Mima’s unraveling psyche in the vein of Mulholland Drive or Black Swan. This 1996 film not only anticipates the reality busting thrillers of the early aughts but also presages the way our identities are splintered across the internet.

Studio Ghibli has brought us moving, remarkable animated films such as Spirited Away, My Neighbor Totoro, and Princess Mononoke. One of Studio Ghibli’s most overlooked movies is Yoshifumi Kondou’s Whisper of the Heart, which finds magic in the ordinary every day. Shizuku is a young girl with great aspirations to become a writer—the only thing stopping her is herself. When she comes across a curious antique shop, she befriends a mysterious boy and his grandfather, who are just the push she needs to look inward and discover her own artistic capabilities.

If you have ever wanted to create something bigger and better than yourself—a story, a song, a poem, a painting, a work of art—then Whisper of the Heart will excite you, will call to you, will remind you to answer your heart’s calling.

Sisters Martine and Filippa, daughters of a founder of a religious sect, live a simple and quiet life in a remote coastal village in Denmark. Throughout the course of their lives, they reject possible romances and fame as part of their commitment to deny earthly attachments. This is upended by the sudden arrival of a French immigrant named Babette, who served as their house help to escape the civil war raging in her country.

Babette’s Feast is an inquiry into simplicity and kindness, and whether these would be sufficient to achieve a life of contentment. The religious undertones perfectly fit with the film’s parable-like structure, where bodily and spiritual appetites are satisfied through a sumptuous feast of love, forgiveness, and gratitude.

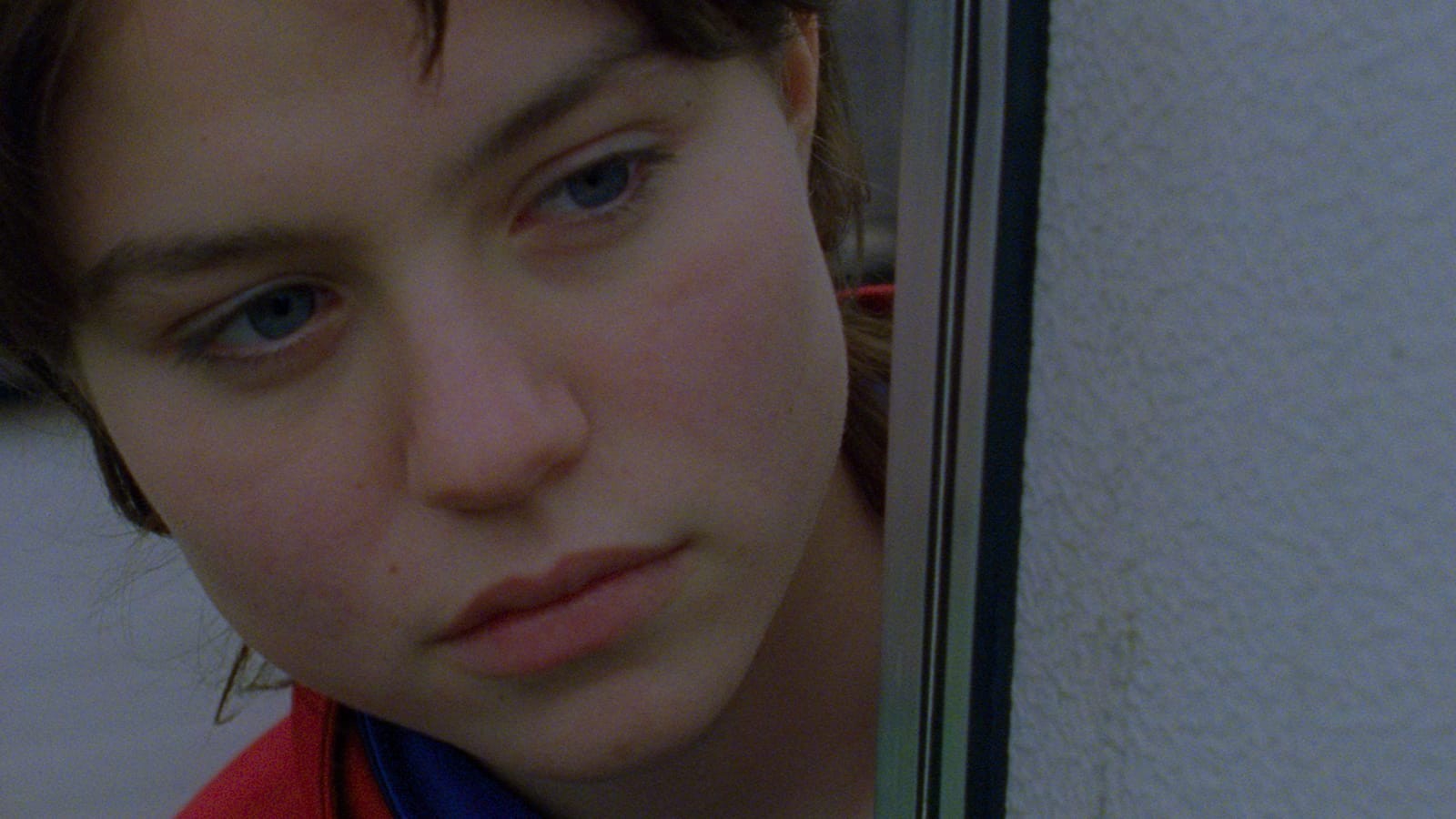

Rosetta begins fiercely, with a shaky handheld camera chasing the eponymous teenager (Émilie Dequenne) as she storms across a factory floor and bursts into a room to confront the person she believes has just lost her her job. The film seldom relents from this tone of desperate fury, as we watch Rosetta — whose mother is a barely functioning alcoholic — fight to find the job that she needs to keep the two alive.

As tough as their situation is, though, Rosetta’s fierce sense of dignity refuses to allow her to accept any charity. A stranger to kindness and vulnerability, her abject desperation leads her to mistake these qualities for opportunities to exploit, leading her to make a gutting decision. But for all her apparent unlikeability, the movie (an early film from empathy endurance testers the Dardenne brothers) slots in slivers of startling vulnerability amongst the grimness so that we never lose sight of Rosetta’s ultimate blamelessness. Its profound emotional effect is corroborated by two things: that it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, and that it helped usher in a law protecting the rights of teenage employees in its setting of Belgium.

There’s something so delightful about watching Good Morning, the second of Yasujirō Ozu’s films in color. It’s easy to see why– the conflict is relatable, Ozu’s shots are immaculately framed in warm colors, and of course, the pouting children hoping to get a television of their own are just pinch-worthy adorable. But through the neighborhood conversations, the different generational concerns of each Hayashi, and a surprising amount of fart jokes, Good Morning subtly ponders on social niceties, the consideration we learn to give to others in silence, as well as the freely given affection that becomes harder to share as adults. Good Morning may not be Ozu’s most famous feature, but it’s nonetheless one of his most delightful to watch.

The sunniest installment of Éric Rohmer’s Tales of the Four Seasons series is a sly, slow burn of a character study. Everything looks sensuously beautiful in the honey-toned French sunshine, except for the ugly egotism of Gaspard (Melvil Poupaud), the full extent of which is gradually revealed over the film’s runtime to amusing — if maddening — effect.

A brooding twenty-something, Gaspard has the traumatic task of having to decide between three beautiful and brilliant young women while vacationing alone on the French coast one summer. He dithers and delays his choice, each woman appealing to a different insecurity of his — but, as frustrating and plainly calculating as he is, you can’t help but be charmed by Gaspard. That’s partly because of Poupaud’s natural charisma, but also because Rohmer grants Gaspard as many searingly honest moments as he does deceitful ones. These come through Rohmer’s hallmark naturalistic walking and talking scenes (a big influence on the films of Richard Linklater), coastal rambles that produce conversations of startling, timeless candor. That inimitable blend of breeziness and frankness is never better matched in the director’s films than by the summer setting of this one, the sharp truths going down a lot smoother in the gorgeous sunlight.

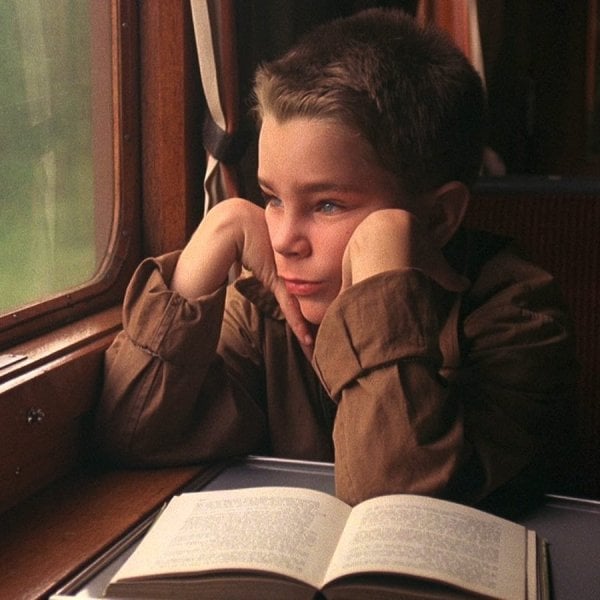

This Swedish surprise hit captivated viewers across the Atlantic because of one thing: the lead’s perspective. Okay, well, the performances are great, the time frame is nostalgic, and it’s grounded by the few incidents that could only happen in a small town. However, at the heart of the story, author and co-screenwriter Reidar Jönsson hones in on Ingemar’s uncertainty and the lack of control over his own fate. Between his mom’s illness, his separation from his older brother, the small space of his uncle’s house, and the fact he can’t even bring his dog, Ingemar is easy to sympathize with, especially as he tries to look towards the brighter side of life. But combined with his future self’s narration, My Life as a Dog cathartically pulls on the painful core memories that could only be made by growing up.

Hayao Miyazaki is no stranger to the fantastical. Howl’s Moving Castle and Spirited Away conjure worlds of spirits and demons, monsters and witches, imaginary wars and extraordinary heroes. But in Kiki’s Delivery Service, the real magic arises from the mundane.

The titular teenaged Kiki leaves home, setting out to become a better witch. She arrives in the idyllic seaside town of Koriko with only her broom and best friend, a black cat named Jiji. When she serendipitously meets Osono, the gentle owner of a bakery, Kiki begins a delivery service as part of her training.

Kiki’s Delivery Service may be one of Miyazaki’s more understated films, but it’s a beautiful reminder that believing in oneself is a magical act of courage that we should all undertake.

Based on the Austrian novel, The Piano Teacher is as brilliant and as disturbed as its protagonist. The film follows Erika Kohut (Isabelle Huppert), the repressed masochist in question, and the trainwreck of a relationship that she develops with her student Walter Klemmer (Benoît Magimel). Their dynamic is undeniably toxic. Austrian auteur Michael Haneke frames each scene with clinical detachment, but it is absolutely brutal how the two characters try to assert control over each other, engage in sadomasochism, and repeatedly violate each other’s boundaries. Huppert’s heartrending performance fully commits to the merciless treatment Erika receives. But more tragic is the way Erika’s unusual relationship could’ve freed her, could’ve helped her process her abuse, and instead, reinforces her repression. It’s scary to make yourself vulnerable by admitting your desires, only for them to be used against you.

The prospect of death puts everything into perspective, but Cléo from 5 to 7 crafted a totally new one altogether. As it says in the title, the titular singer wanders the French capital in real time, with an ominous tarot card reading turning Cléo’s world into black and white, shifting the mood even as she tries to ease the worry by going through her regular day-to-day. But as she does so, filmmaker Agnès Varda crafts memorable images that subtly depict Cléo’s inner world. The camera pivots, swaps angles, changes point of view, and only moves into the conventional images and score when Cléo performs, whether that be in literally practice of her craft, or in the presence of other people depending on the role she plays in their life. It’s this thoughtful use of the camera, gaze, and of time itself that makes Cléo from 5 to 7 a standout drama from the French New Wave.

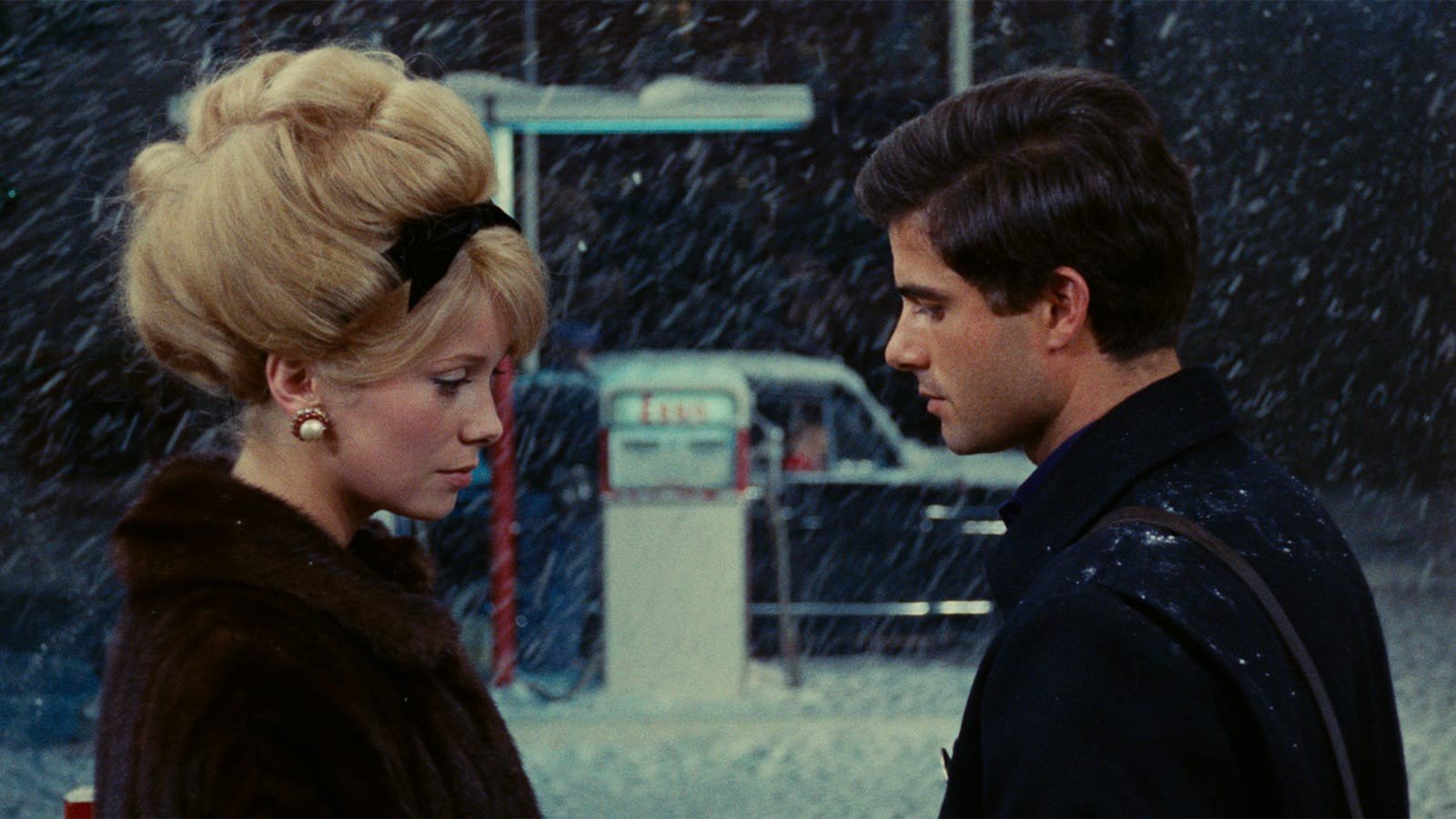

If we were to list down the best of the best movie musicals ever made, most of the titles would probably come from the Golden Age of Hollywood. But we’d be remiss to forget that just a few years later, all the way across the pond, came The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, a French romantic musical from Jacques Demy. It’s certainly in the running for the most gorgeous musical ever made, with the bold, dreamy colors, incredible camera work, stylish costumes, and two beautiful leads front and center, but what makes Cherbourg great is the lush composition made by Michel Legrand. With the sweeping violins and the tragic lyrics of Devant le Garage, to the catchy, jazzy Scène du Garage that starts off the film, Les Parapluies de Cherbourg brings together sublime visuals and sound into one of the greatest musicals ever made.

If you’re living alone and just came back home from a bad day, Wolf Children can make you feel like everything’s alright. It’s the kind of movie that feels like a warm hug and one that you will likely bookmark to get back to for this exact reason. Co-written and directed by Mamoru Hosoda, who’s most known for The Girl Who Leaps Through Time, the title is to be taken without any salt: it tells the, allegedly true, story of a woman raising children who are half-human and half-wolf. It all starts with Yuki studying at Tokyo University, where she meets a mysterious and handsome young man, who can turn into a wolf at will. They fall in love and have children inheriting this strange skill. This is where the colorful visuals and life-affirming vibe of this anime give way to a bleak narrative turn. Wolf Children is a strange story of love and parenting told in an imitable style.

Frequently considered one of the greatest animated movies of all times, and certainly the highest-grossing film in Japanese history, Spirited Away is Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli at their very best. It was also the first non-English animation movie to win an Oscar. On the surface, it’s a film about a Chihiro Ogino (Hiiragi), a young girl who stumbles into an abandoned theme park with her parents. In a creepy spiritual world full of Shinto folklore spirits, she sees all kinds of magic and fantastic creatures, while having to find a way to save her parents and escape. In addition to the adventure, the coming-of-age theme, and the motifs of ancient Japanese lore, the film can also be understood as a critique of the Western influence on Japanese culture and the struggle for identity in the wake of the 1990s economic crisis. A deep, fast-paced, and hypnotizing journey.

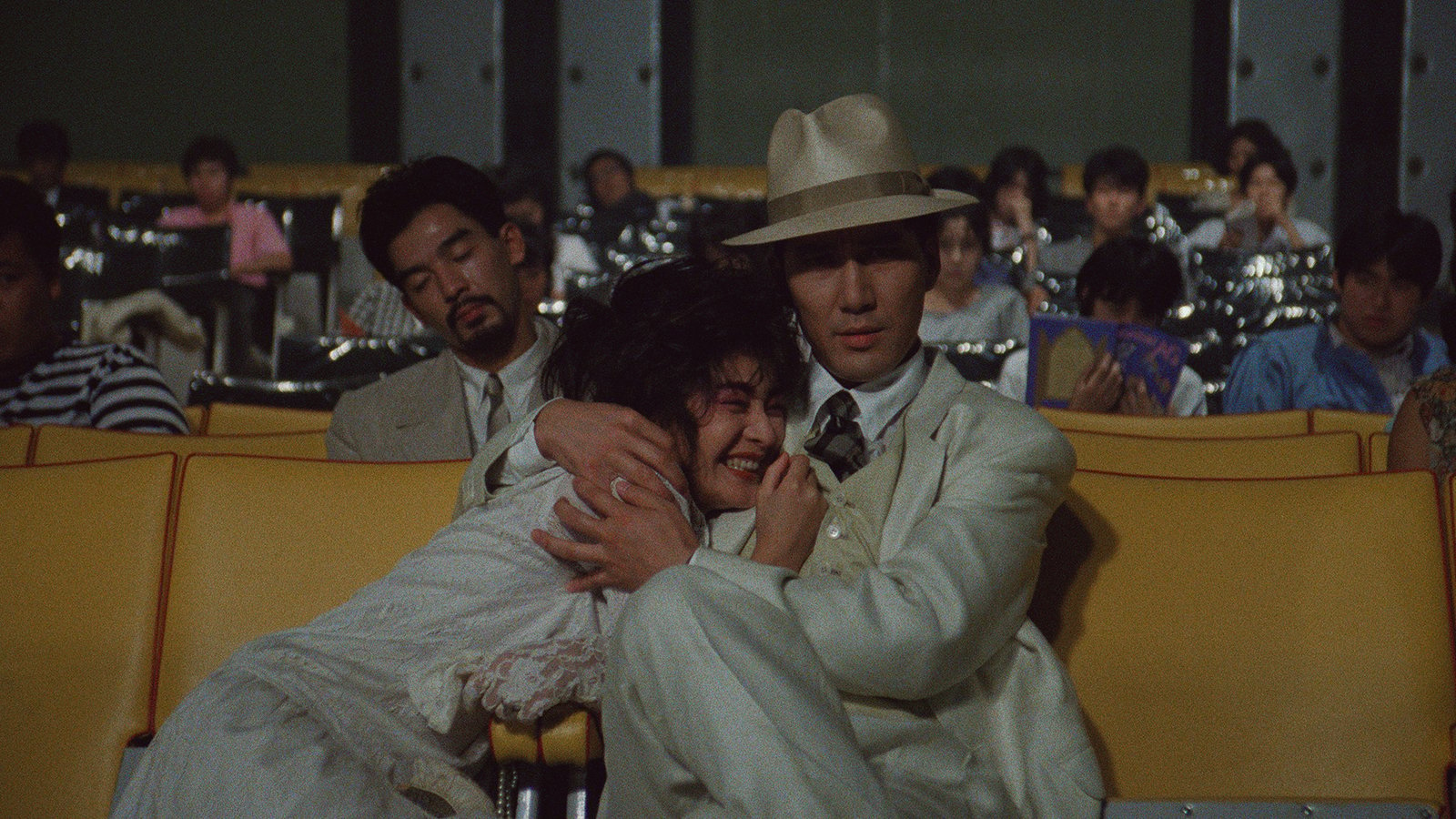

While billed as a “ramen western”, Tampopo satirizes plenty of other American genres, including, but not limited to: 1) the inspirational sports film, with Tampopo’s diligent training, 2) the erotic, arthouse drama through its egg yolk kiss, 3) the witty, social comedy pointing out the absurd in dinnertime tables, and 4) the melodramatic mafia romance with its room-serviced hotel getaway. But the film doesn’t buckle under the weight of carrying all these genres– instead, the customer vignettes are all delicately plated to balance out the hearty journey of a store owner learning about ramen and the bemused, yet cohesive contemplation about food. Tampopo is one of a kind.

Called a masterpiece by many and featured on many best-of-the-21st-century lists, Director Wong Kar-wei has created a thing of singular beauty. Every frame is an artwork (painted, as it were, with help of cinematographer Christopher Doyle) in this meticulously and beautifully crafted film about the unrequited love of two people renting adjacent rooms in 1960s Hong Kong. These two people, played by Tony Leung and Maggie Cheung, struggle to stay true to their values rather than give in to their desires, while they both suspect their spouses of extramarital activities. The flawless acting, stunning visuals, and dream-like beauty of In the Mood for Love perfectly captures the melancholy of repressed emotions and unfulfilled love. The cello motif of Shigeru Umebayashi’s main theme will haunt you long after you finished watching.

Based on a classic Japanese folktale, Isao Takahata’s last film will break your heart. This adaptation, of course, follows Princess Kaguya from her being discovered in a glowing bamboo stalk to her departure to the moon. However, while faithful to the original tale, Takahata’s direction turns this historical fantasy into a heart-wrenching coming-of-age film as ethereal as the titular character. The film doesn’t focus on the crazy pursuit of her suitors; instead, we’re drawn to the simple experiences Kaguya herself is drawn to and wants more of, as she tries to balance her life with the societal expectations places on women. All of which is rendered through the film’s lush watercolored scenes of the blowing wind or the opening of plum blossoms.

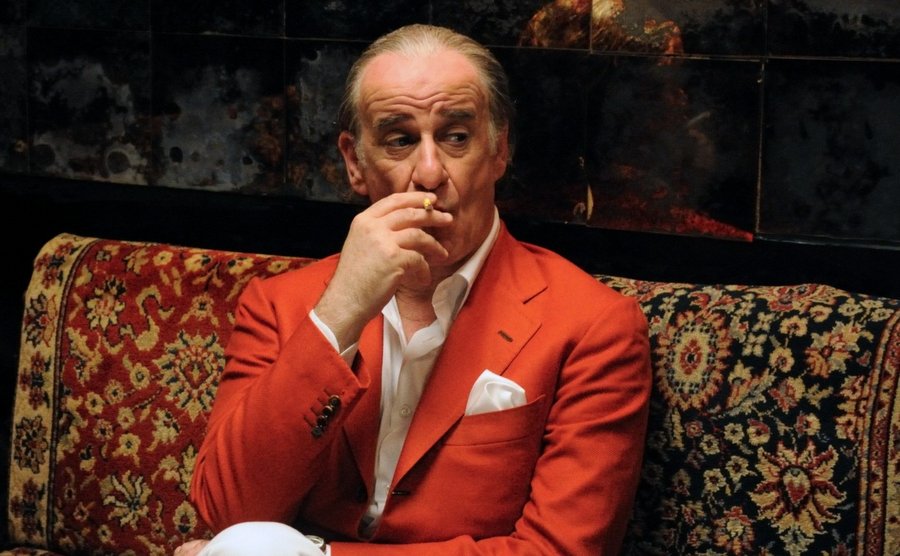

The Great Beauty is a film of superlatives! Originally titled La Grande Bellezza, this movie by Italian star director Paolo Sorrentino is so replete with lush, opulent cinematography, it sometimes borders on sensory overload. Having won Best Foreign Language Film at the 86th Academy Awards, as well as the Golden Globe, and the BAFTA award in the same category, The Great Beauty is also a critics’ darling and an award-show sweeper – in addition to being hailed as Paolo Sorrentino’s greatest work to date.

Essentially a tragicomedy, it is both a study and a celebration of the hedonism and decadence of its main protagonist – the bon-vivant and modern-day Roman socialite Jep Gambardella (played by an electrifying Toni Servillo). Instead of honing the craft of writing, Gambardella at some point decides to become the self-proclaimed “king of high life” of Rome. After his 65th birthday, he experiences a shock that changes him for good, prompting him to look past the parties and the nightclubs and to discover the sublime beauty of his hometown, the eternal city. In this way, The Great Beauty is a meditation on art, regret, and pleasure – and Sorrentino’s love letter to Rome.