15 Best French Movies on Hulu

It would be easy to stereotype the typical French film as “weird.” But the French have long earned the right to experiment and to have their experiments influence the rest of the global film industry, given their cinematic history dating back to the very, very first movies ever made. And a great streaming service to find French productions or co-productions that try doing things a little differently is Hulu, whose selection is already typically more offbeat and more independent than its most closely affiliated streamers like Disney Plus. Below we’ve put together a list of little-known but high-quality movies on Hulu that you may or may not have known were French, too.

This anthology of 18 short films — directed by the likes of the Coen brothers, Gurinder Chadha, Wes Craven, and Olivier Assayas — is a cinematic charcuterie board. Each director offers their own creative interpretation of one north star: love in Paris. Romantic love is heavily represented, naturally, but in diverse forms: love that’s run its course, dormant love in need of rekindling, electric chance encounters, and, apt given the location, honeymoon love. Segments like the one starring Juliette Binoche and Alfonso Cuarón’s five-minute-long continuous take opt to focus on parental love instead, with the former also exploring love through the frame of grief.

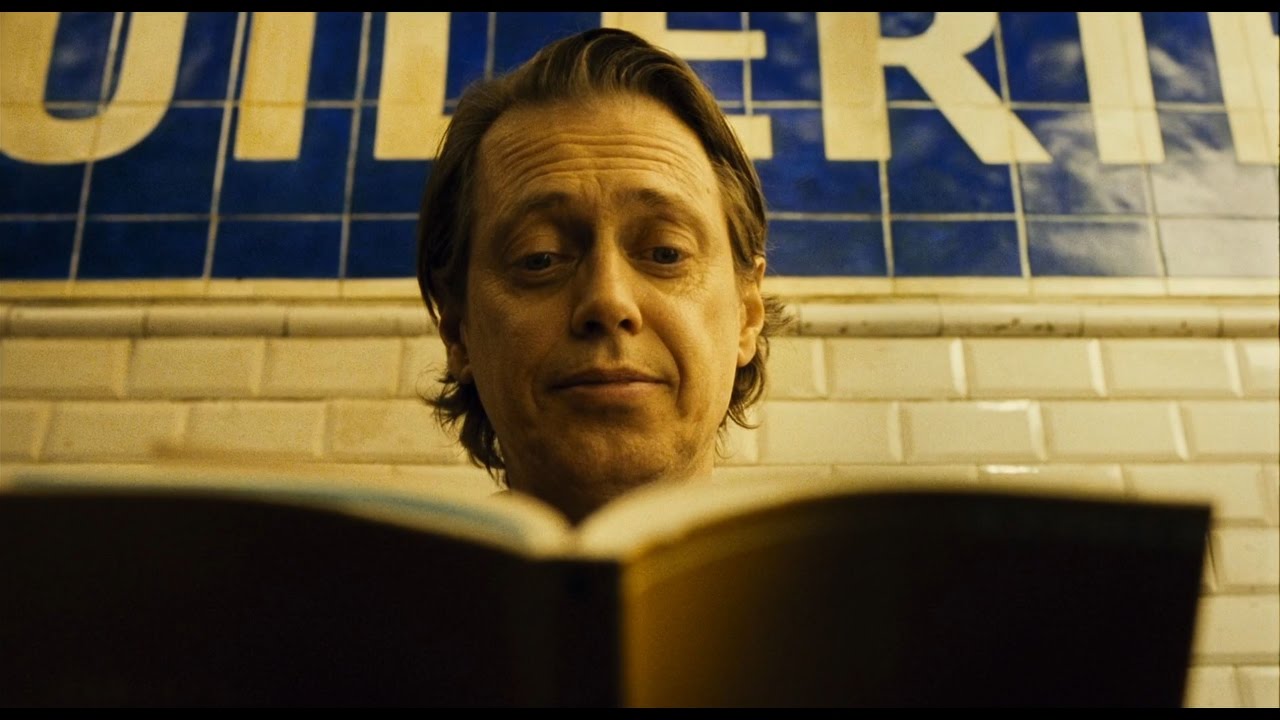

If this all sounds a little syrupy and sentimental, fear not: there are dashes of bubble-bursting humor from the Coens, whose short stars a silent Steve Buscemi as a stereotypically Mona Lisa-obsessed American tourist who commits a grave faux pas in a metro station. Instead of sightseers, some directors offer more sober reflections on the experience of migrants in the city, which help ground the film so it doesn’t feel quite so indulgent. Still, the limited runtime of each vignette (sub-10 minutes) doesn’t let any one note linger too long, meaning the anthology feels like a series of light, short courses rather than a gorge of something sickly.

If it’s true that to cook is to love, then Dodin and Eugenie must be enraptured by one another. They use the exquisite language of food to express their feelings for one another, and watching their exchange, you can’t help but feel honored, if not embarrassed, to witness such an intimate and love-filled act. Food is everywhere here, delicately prepared and sumptuously consumed, but the film is more than just a glorified Food Network program. It’s a painting come to life, a love letter to craft, and a beautiful example of a life fully lived.

At 80 minutes, Smoking Causes Coughing is another slice of perfectly paced absurdist fun from Quentin Dupieux, the zany mind behind Rubber (in which a car tire turns serial killer) and Deerskin, the tale of a motorcycle jacket that wants to rule the world. This time around, the protagonists aren’t inanimate objects: they’re Tobacco Force, a Power Rangers-style band of lightly idiotic superheroes who harness the toxic power of cigarettes to defeat Earth’s enemies, and are each named after one of their harmful components (Benzene, Nicotine, Mercury, Ammonia, and Methanol). They’re led by Chief Didier, a rat who inexplicably dribbles green goo — and, even more inexplicably, casts an intense erotic spell over Tobacco Force’s female members.

Smoking Causes Coughing leans deliriously, hilariously far into its absurdist premise. Citing a lack of “group cohesion,” Chief Didier sends the Force to the woods on a team-building retreat. While they swap “scary” stories over a campfire, however, a reptilian galactic supervillain plots to put Earth “out of its misery” because it’s a “sick planet” (can’t really argue with that). Full of insane plot twists and without a tired trope in sight, Smoking Causes Coughing never approaches the realm of predictability — no small achievement in this era of superhero fatigue.

Among the sea of class satires released in the last year, Triangle of Sadness is one of the better ones. Directed by Ruben Östlund (The Square, Force Majeure), the film follows an ultra-rich group of people who get stranded on an island after their luxury cruise ship sinks. The social pyramid that has long favored them suddenly turns upside down when a crew member (a glowing Dolly de Leon) effectively runs the group of sheltered castaways.

Triangle of Sadness may not be as sharp as Östlund’s previous work, and it may not add anything particularly new to the saturated discussions of social class, but it remains a darkly humorous and engaging watch, masterfully helmed by a strong script and ensemble.

In 1961, Francisco de Goya’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington was stolen from London’s National Gallery, but the theft was no slick heist pulled off by international art thieves. No, the improbable culprit was (the improbably named) Kempton Bunton, a retired bus driver and aspiring playwright who pinched the painting — which the gallery had recently acquired for £140,000 of UK taxpayers’ money — as a Robin Hood-esque “attempt to pick the pockets of those who love art more than charity.” The principled Bunton (played here by Jim Broadbent) was, at the time, waging a one-man campaign to convince the government to grant pensioners and veterans free TV licenses, and the Goya theft was his way of publicizing those efforts. It was an eccentric plan, but Broadbent leans fully into his status as a UK national treasure here, making oddball Bunton a deeply sympathetic and warm figure because of (not despite) those quirks. Thanks to his performance — and the note-perfect direction of the late, great Roger Michell — a quirky footnote of history becomes a sweet, unexpectedly moving story about solidarity and the power of the underdog.

The Square is a peculiar movie about a respected contemporary art museum curator as he goes through a few very specific events. He loses his wallet, his children fight, the art he oversees is does not make sense to an interviewer… Each one of these events would usually require a precise response but all they do is bring out his insecurities and his illusions about life. These reactions lead him to very unusual situations. A thought-provoking and incredibly intelligent film that’s just a treat to watch. If you liked Force Majeure by the same director, The Square is even better!

This is a hilarious political comedy starring the ever-great Steve Buscemi. Set in the last days before Stalin’s death and the chaos that followed, it portrays the lack of trust and the random assassinations that characterized the Stalinist Soviet Union. Think of it as Veep meets Sacha Baron Cohen’s The Dictator. Although to be fair, its dark comedy props are very different from the comedy that comes out today: where there are jokes they’re really smart, but what’s actually funny is the atmosphere and absurd situations that end up developing.

To plenty of countries around the globe, democracy has become so ubiquitous that we forget it’s relatively new, at least relative to the rest of human history. Bhutan is one of the last countries that became a democracy, and writer-director Pawo Choyning Dorji chose to depict a slice of how they made the shift in The Monk and the Gun. As Tashi sets out to obtain two weapons for his mentor, and Ron seeks a specific antique gun, Dorji presents slice-of-life moments of the beautiful Bhutan countryside, intercut with the subtle ways tradition still persists amidst modernity, and the funny ways change can clash with culture. It’s no wonder The Monk and the Gun was chosen as the Bhutanese entry for the Best International Feature at the 96th Academy Awards.

La Chimera is often meandering. Scenes flitter about and move at different paces, resembling dreams more than they do reality, but they’re hardly trivial. Just the opposite, they enchant you with their beauty and confront you with deep, existential questions that haunt you long after the film’s run. You won’t find obvious answers here though, and you might even leave more perplexed than when you began. But that is the beauty of a film like La Chimera, it cracks you open to different realms and possibilities.

The Seed of the Sacred Fig bravely takes on the increasingly violent patriarchy and theocracy in modern-day Iran. It follows a family of four—Iman, Najmeh (Soheila Golestani), Rezvan (Mahsa Rostami), and Sana (Setareh Maleki)—and reveals how the political can creep into the personal. Iman, the father, has just been promoted at work (he’s one step closer to being a judge), while his two daughters are budding revolutionaries. The educated girls see through the lies of state television and challenge their conservative parents’ ideas on government and religion. It sounds straightforward, but director Mohammad Rasoulof lets everything unfold subtly and sharply. By the second half, the film transforms into a slow-burn thriller as the family home becomes a microcosm of Iran itself. It’s a brave film helmed by even braver people. Rasoulof and his cast, who filmed in secret to avoid the film ban in Iran, had to escape to Europe after they were interrogated and sentenced in their home country. The Seed of the Sacred Fig can’t encapsulate the entirety of Iran’s troubles, nor does it try, but it’s a good place to start.

You would expect a courtroom drama to be built around damning pieces of evidence, passionate speeches, or certain social issues lending weight to the investigation. But what makes Justine Triet’s Palme d’Or-winning Anatomy of a Fall so remarkable is how direct it is. Triet doesn’t treat this case like a puzzle for the audience to participate in solving; instead she fashions this trial into a portrait of a family being eroded by even just the suggestion of distrust. It ultimately has far less to do with who’s responsible for the death of a man, and more to do with the challenge of facing the reality that the people we love are capable of being cruel and callous to others.

Which isn’t to say that Anatomy of a Fall doesn’t still possess qualities that make it a great courtroom drama—doubt only continues to pile up with every new piece of information that’s revealed to the audience, until we begin to interpret characters’ expressions and actions in a contradictory ways. But the way Triet executes these reveals is just so skillful, choosing precisely how to let details slip and obscuring everything behind faulty memory, intentional dishonesty, or any other obstacles that usually come up during an investigation.

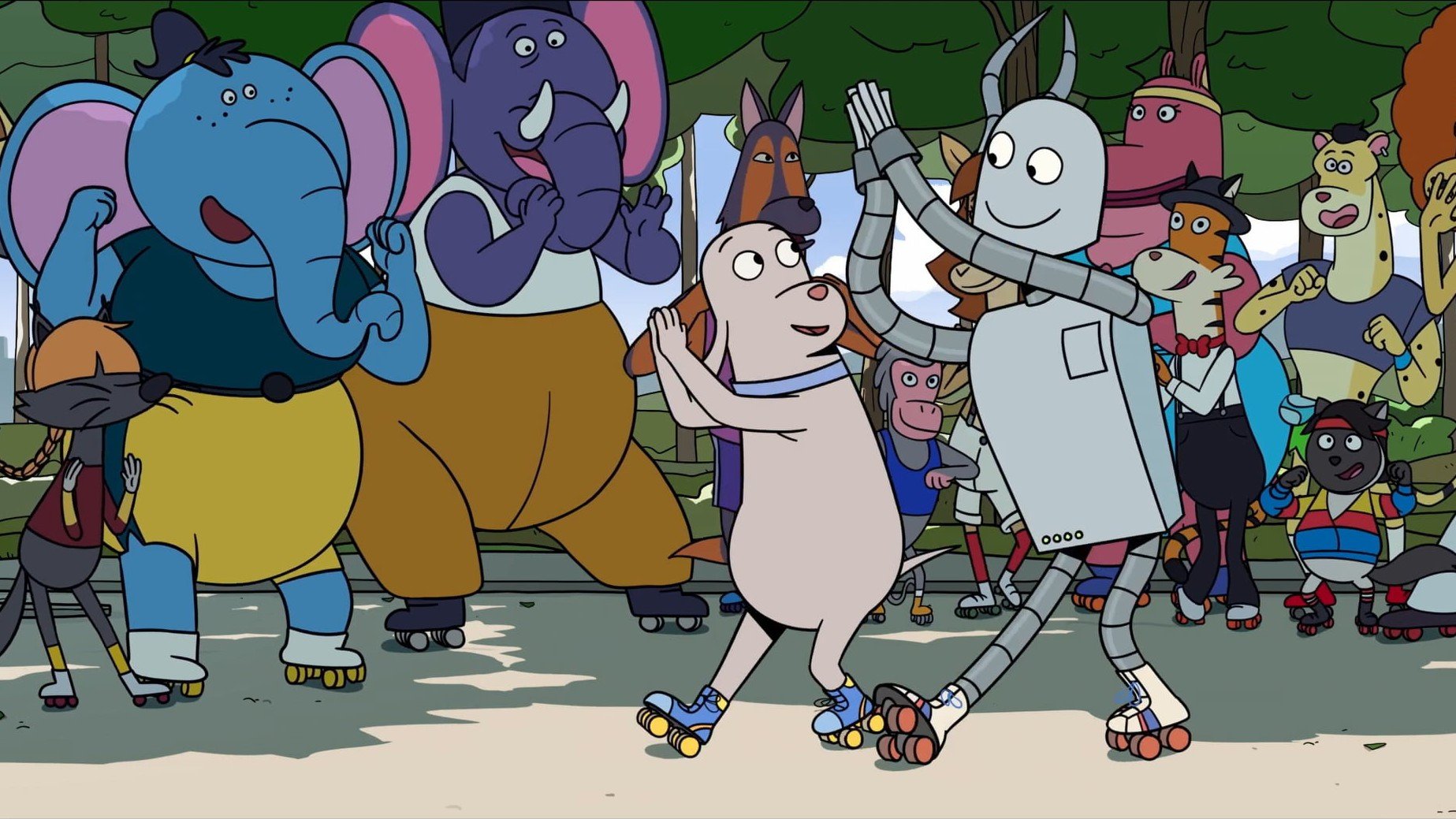

The first few minutes of Robot Dreams are so deceptively simple and pleasant that it’s hard to think of a conflict that could keep the film moving. But something does happen—life happens, which sounds annoyingly vague, but it’s true. Life happens, and the rest of the film is about how Dog and Robot survive the specific pain of living. It’s at once poignant and delightful, filled with surprising moments that shouldn’t work, but do. It feels incredibly human even though there are no people in sight. It says a lot about the crisis of loneliness and the importance of moving on even though it’s a silent movie. And then there’s that one scene that breaks the fourth wall most adorably, proving that Robot Dreams is anything but the straightforward film it seemed to be in the beginning. Consistently, however, it is a touching movie. Whether it ends up breaking or warming your heart is just something you have to look out for.

In a world where mortality has been overcome, people watch in awe as the as the 118-year-old Nemo Nobody, the last mortal on Earth, nears his end. He is interviewed about his life, recounting it at three points in time: as a 9-year-old after his parents divorced, when he first fell in love at 15, and as an adult at 34. The three stories seemingly contradict each other. Utilizing non-linear cinematography, Belgian director Jaco Van Dormael presents each of these branching pathways as a version of what could have been. The result is a complex, entangled narrative. That and the movie’s ensemble cast, featuring Jared Leto, Sarah Polley, and Diane Kruger, have turned Mr. Nobody into a cult classic. The soundtrack, featuring several of the beautifully restrained music by Eric Satie, is also considered a masterpiece. While it is surely not for everybody, this is trippy, intimate, and existential sci-fi at its best.

More simply called La Vie d’Adèle in its native language, this French coming-of-age movie was hugely successful when it came out and was probably one of the most talked-about films of the time. On the one hand, the usual puritans came to the fore, criticizing the lengthy and graphic sex scenes. On the other hand, Julie Maroh, who wrote the source material that inspired the script, denounced Franco-Tunisian filmmaker Abdellatif Kechiche for directing with his d*ck, if you don’t mind me saying so, while also being an on-set tyrant. Whatever you make of this in hindsight, the only way to know is to watch this powerfully acted drama about the titular Adèle (Adèle Exarchopoulos), and her infatuation with Emma, a free-spirited girl with blue hair, played by Léa Seydoux. The film beautifully and realistically portrays Adele’s evolution from a teenage high-school girl to a grown, confident woman. As their relationship matures, so does Adèle, and she slowly begins to outgrow her sexual and philosophical mentor. Whatever your final verdict on the controversial sex scene, Blue Is the Warmest Color is without doubt an outstanding film as are the performances from Exarchopoulos and Séydoux.

Nothing about Saint Omer is easy. A female Senegalese migrant (Guslagie Malanga) is put to trial for committing infanticide, but throughout the film, it becomes clear how much of a victim she is too, of an uncaring and deeply prejudiced society. “What drove her to madness?” Her attorney asks at one point. We’re not sure. We’re not necessarily asked to side with her, nor answer the many hard-hitting questions brought up in the film, but we sit with the uneasiness of it all and, in that silence, confront our ideas about motherhood, womanhood, personhood.

This confusion is what makes the film so compelling. Despite the court’s best efforts, Laurence isn’t meant to be understood. She’s meant to be an example of the ever-ambiguous, forever-complicated, always-hurt person. It’s human nature after all to be this complex and messed up. The film shows us that the best that we can do in situations like this is to listen, understand, and as our protagonist Rama (Kayije Kagame) does, make peace with the noise.