40 Best Foreign-Language Movies on BFI Player UK

January 24, 2025

Share:

Looking to expand your cinematic palate with more international films? Lucky for you, there are several streaming services dedicated to curating a selection of relatively smaller films—especially those not in the English language—including the Criterion Channel, Mubi, and BFI Player. Brought to us by the British Film Institute, BFI Player gives you access to a deep bench of gems throughout film history, as well as those that have been making waves on the international circuit in recent years. To get you started on your foreign film journey, we’ve listed a number of non-English language films on the service that should remind you just how much there is to explore in cinema outside of Hollywood and the UK’s English-speaking industries.

Read also:

11. Capernaum (2018)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

Capernaum is both the highest-grossing Middle Eastern movie of all time and the highest-grossing movie in Arabic of all time. Lebanese director Nadine Labaki was the first female Arab director to be nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the Academy Awards. Capernaum is thus duly considered a masterpiece, as it follows an angry 12-year-old kid in Lebanon, who leaves his negligent parents and tries to make it in the streets on his own. It’s a tale of grinding poverty as experienced by a boy with a good heart, who meets many kindly people on the way as well as sinister characters. An acting tour de force by the fierce child actors, especially Zain Al Rafeea, Capernaum is harrowing, emotional, and, maybe, a touch melodramatic. However, it doesn’t compromise when asking some hard questions about parental failure and love, putting them into the context of the bigger regional picture. It can be a tough watch, but the furious acting and pitch-black humor, ultimately, make this an uplifting movie, likely to stir up some debate.

12. Still Walking (2008)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

Koreeda is a master of the tender gaze. He deals so softly, elegantly, and emphatically with the characters in his films, it will make you feel like you’re watching life itself in all its complex, emotional splendor. Maybe this is particularly true for this movie because it has been inspired by Koreeda’s memories of his own childhood and the passing of his mother. Still Walking is a quietly toned movie spanning a period of 24 hours in the life of the Yokoyama family, as they gather to commemorate the passing of their eldest son. At the center of the story is the father, an emotionally distant man who commands respect both from his family and community. Opposite from him sits the other son, the black sheep, who seeks his father’s validation. Directed, written, and edited by Koreeda, this dynamic is one of many in this slice-of-life movie about how families deal with loss. And, however distant the culture or setting in Japan may seem to the outsider, you’re bound to recognize either yourself or your family among the tender scenes of this masterful drama.

13. Saint Omer (2022)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

Nothing about Saint Omer is easy. A female Senegalese migrant (Guslagie Malanga) is put to trial for committing infanticide, but throughout the film, it becomes clear how much of a victim she is too, of an uncaring and deeply prejudiced society. “What drove her to madness?” Her attorney asks at one point. We’re not sure. We’re not necessarily asked to side with her, nor answer the many hard-hitting questions brought up in the film, but we sit with the uneasiness of it all and, in that silence, confront our ideas about motherhood, womanhood, personhood.

This confusion is what makes the film so compelling. Despite the court’s best efforts, Laurence isn’t meant to be understood. She’s meant to be an example of the ever-ambiguous, forever-complicated, always-hurt person. It’s human nature after all to be this complex and messed up. The film shows us that the best that we can do in situations like this is to listen, understand, and as our protagonist Rama (Kayije Kagame) does, make peace with the noise.

14. No Bears (2022)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

The Iranian director Jafar Panahi has faced constant persecution from his country’s government for over a decade, for his career of sharply political films speaking truth to power. In fact, No Bears—which was shot in secret, in defiance of the government banning him from filmmaking for 20 years—had its initial festival run in 2022 while Panahi was in prison. Evidence of Panahi’s drive to keep making his movies, no matter what, are clear in this film’s limited resources and occasionally inconsistent video quality. But even those obstacles can’t get in the way of his vaulting ambition.

No Bears operates on several different layers that all express Panahi’s growing frustration with—but also his commitment to—making art that only ever seems to put himself and other people in harm’s way. At its base level, this is a suspenseful small-town thriller, as an exiled Jafar Panahi (playing himself) tries to evade suspicion from the villagers around him. At the same time, Jafar is struggling to direct a film remotely, which creates a strain on his production crew. On top of that, the characters in his film undergo their own drama, seeking asylum out of Turkey. All of this is edited together under a stirring screenplay written with heart, humor, and the hope that the institutions that try to scare us will never keep us in the dark forever.

15. BPM

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

Autobiographical in nature, 120 BPM is French screenwriter Robin Campillo’s first feature film. It revolves around the Parisian chapter of the AIDS advocacy group ACT UP, which Campillo was a member of in the early 1990s, and the love between Nathan, the group’s newest member, who is HIV negative, and Sean, one of its founding and more radical members, who is positive and suffers the consequences of contracting AIDS. Using fake blood and spectacular direct action, ACT UP advocated more and better research of treatment, prevention, and awareness. This was at a time when many, implicitly or explicitly, viewed AIDS as a gay disease, even as a punishment for the gay community’s propensity to pleasure and partying. The latter is reflected by the film’s title, 120 bpm being the average number of beats per minute of a house track. Arnaud Rebotini’s original score echoes the ecstasy-driven house music hedonism of the time with some effective original cuts, albeit with a melancholic streak. Because, for all the love, friendship, and emotion of the ACT UP crew that BPM so passionately portrays, anger and sadness pervade the lives of these young people as the lack of effective treatment threatens to claim the lives of their loved ones.

16. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy (2021)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

From Drive My Car director Ryusuke Hamaguchi comes another film featuring long drives, thoughtful talks, and unexpected twists. An anthology of three short stories, Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy ponders over ideas of love, fate, and the all-too-vexing question, “what if?”

What if you didn’t run away from the one you love? What if you didn’t give in to lust that fateful day? What if, right then and there, you decide to finally forgive?

Big questions, but without sacrificing depth, Hamaguchi does the incredible task of making every single second feel light and meaningful. Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy will leave you with mixed emotions: excited, startled, dejected, hopeful. But one thing you won’t feel is regret over watching this instant classic of a film.

17. Maborosi (1995)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

Director Hirokazu Kore-eda’s feature debut is nothing short of a masterpiece, his style of serenity apparent from the get-go. With Kore-eda’s still frames and touching, relatable stories, it’s almost impossible not to find yourself caring for his characters like they are your own family.

In Maborosi, Yumiko (Makiko Esumi) is haunted by one loss after another and struggles to accept these tragedies and move on with her life. Her story is probably the toughest Kore-eda has had to tell, yet there is still a certain beauty to it, especially in its quietness and moody atmosphere. Not forcing any of his characters’ feelings on the audience, Kore-eda manages to tell a harrowing tale in the gentlest of ways.

18. 5 Broken Cameras (2011)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

In 2005, Palestinian olive farmer Emad Burnat bought a camera to document the birth of his new son, Jibreel. But what was intended as an act of celebration quickly grew into something else, as Burnat inadvertently became a documentarian of the oppression his West Bank village faced when a wall was erected through it and Palestinian farmland illegally appropriated by Israeli settlers. As we come to witness, this reluctant pivot is just another example of everyday life in Bil’in being forcibly reoriented by the occupation, as Burnat captures the daily struggles of life in the village and charts the innocence-shattering effect the occupation has on young Jibreel’s burgeoning consciousness.

Over his footage of encroaching illegal settlements, the arrests of Palestinian children in the middle of the night, the point-blank shootings of blindfolded and handcuffed peaceful protestors — plus tender snapshots of nature and joyful events in the village — Burnat delivers a poetic, reflective narration that miraculously ties these horrible and hopeful images together. It’s this intimacy of perspective that makes 5 Broken Cameras profoundly harrowing and unexpectedly transcendent — a personal document of oppression that is also a testament to the miraculous persistence of the human spirit, the resilience of life and the urge to seek beauty even under truly awful circumstances.

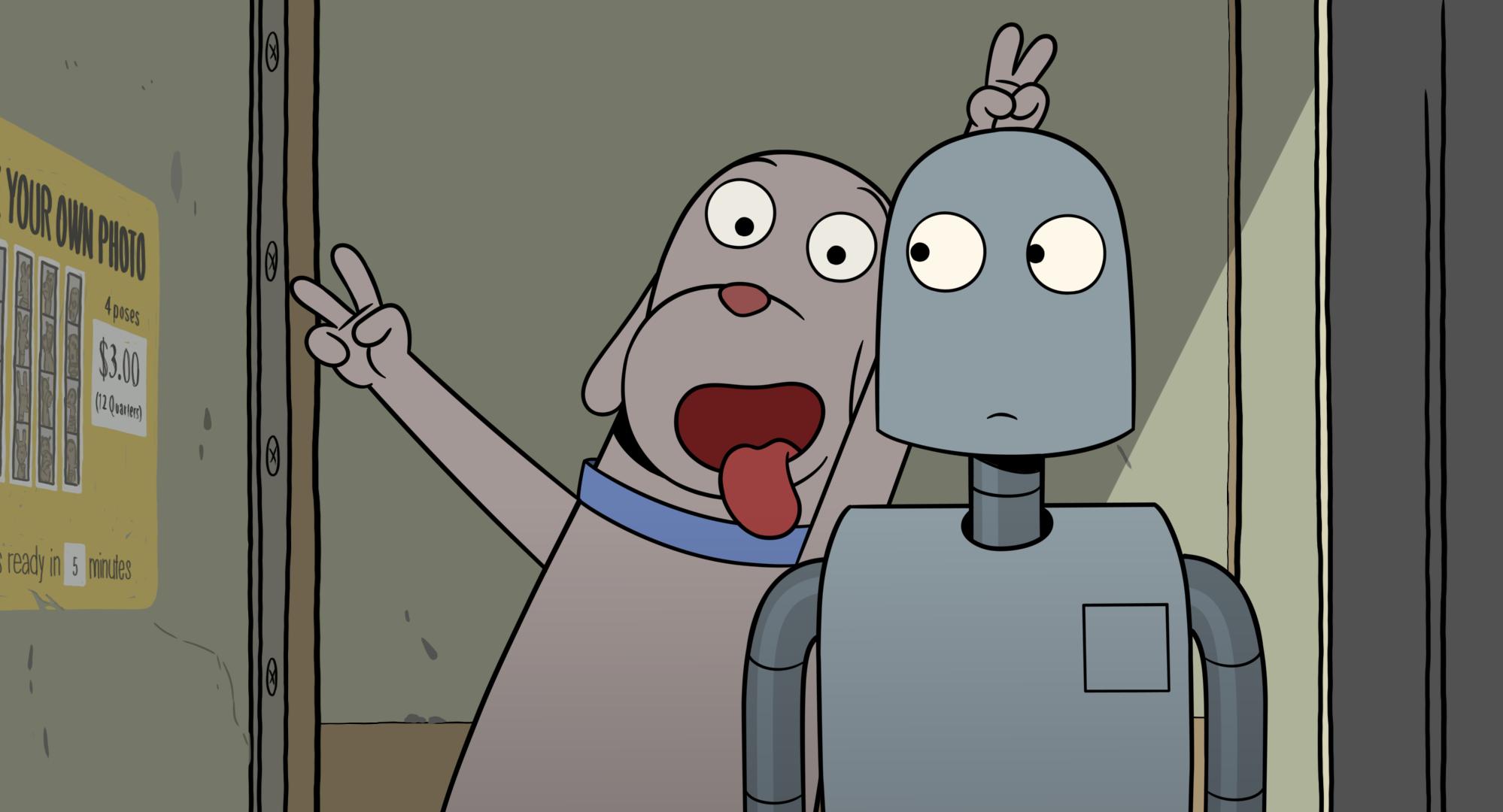

19. Robot Dreams (2023)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

The first few minutes of Robot Dreams are so deceptively simple and pleasant that it’s hard to think of a conflict that could keep the film moving. But something does happen—life happens, which sounds annoyingly vague, but it’s true. Life happens, and the rest of the film is about how Dog and Robot survive the specific pain of living. It’s at once poignant and delightful, filled with surprising moments that shouldn’t work, but do. It feels incredibly human even though there are no people in sight. It says a lot about the crisis of loneliness and the importance of moving on even though it’s a silent movie. And then there’s that one scene that breaks the fourth wall most adorably, proving that Robot Dreams is anything but the straightforward film it seemed to be in the beginning. Consistently, however, it is a touching movie. Whether it ends up breaking or warming your heart is just something you have to look out for.

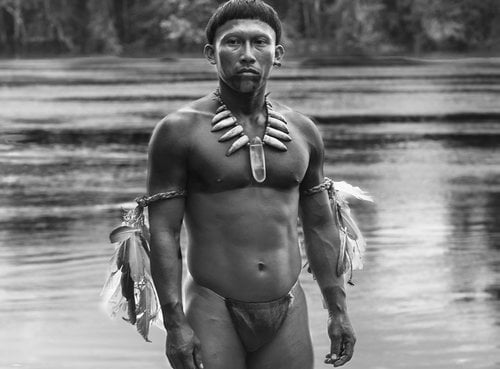

20. Embrace of the Serpent (2015)

Genres

Director

Actors

Moods

This movie is gentle and utterly chaotic, intimate and massive, beautiful and ugly… it tries to be so many things and somehow pulls it off. It tells two stories parallel in time, based on the real-life diaries of two European scientists who traveled through the Amazon in the early and mid-twentieth century. Their stories are some of the only of accounts of Amazonian tribes in written history. The main character and guide in the movie is a shaman who met them both. At times delicate to the point of almost being able to feel the water, at times utterly apocalyptic and grand… to watch this movie is to take a journey through belief systems, through film… and to be brought along by cinematography that is at times unbelievably and absurdly beautiful. Meditative, violent, jarring, peaceful, luminous, ambitious, artful, heavy handed, graceful… it’s really an incredible film.

Read also:

Comments

Add a comment

Ready to cut the cord?

Here are the 12 cheapest Live TV streaming services for cord-cutting.

More lists

Lists on how to save money by cutting the cord.

Curated by humans, not algorithms.

© 2025 A Good Movie to Watch. Altona Studio, LLC, all rights reserved.