He Got Game (1998)

The Very Best

8.3

Movie

TLDR

Spike Lee shoots, Spike Lee scores.

What it's about

The take

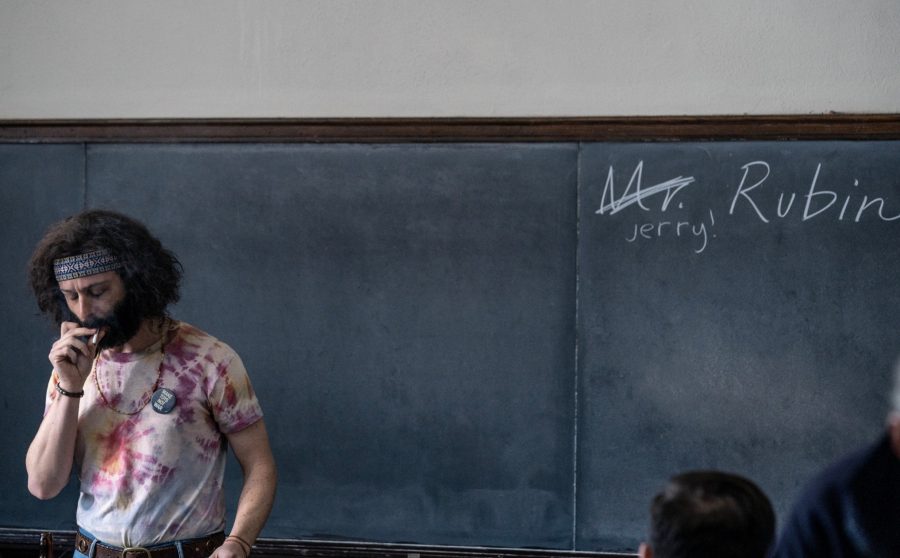

There’s a vein of reality running through He Got Game that gives this Spike Lee joint a sense of pulsating immediacy. For one, the young basketball prodigy at its center is played by real-life pro Ray Allen, who shot the movie during the sport’s off-season period in 1997. The film also draws on a host of other ballers and ancillary figures — including coaches and commentators — to fully convince us of the hype around Jesus Shuttlesworth (Allen), a Coney Island high-schooler who’s been crowned America’s top college draft pick.

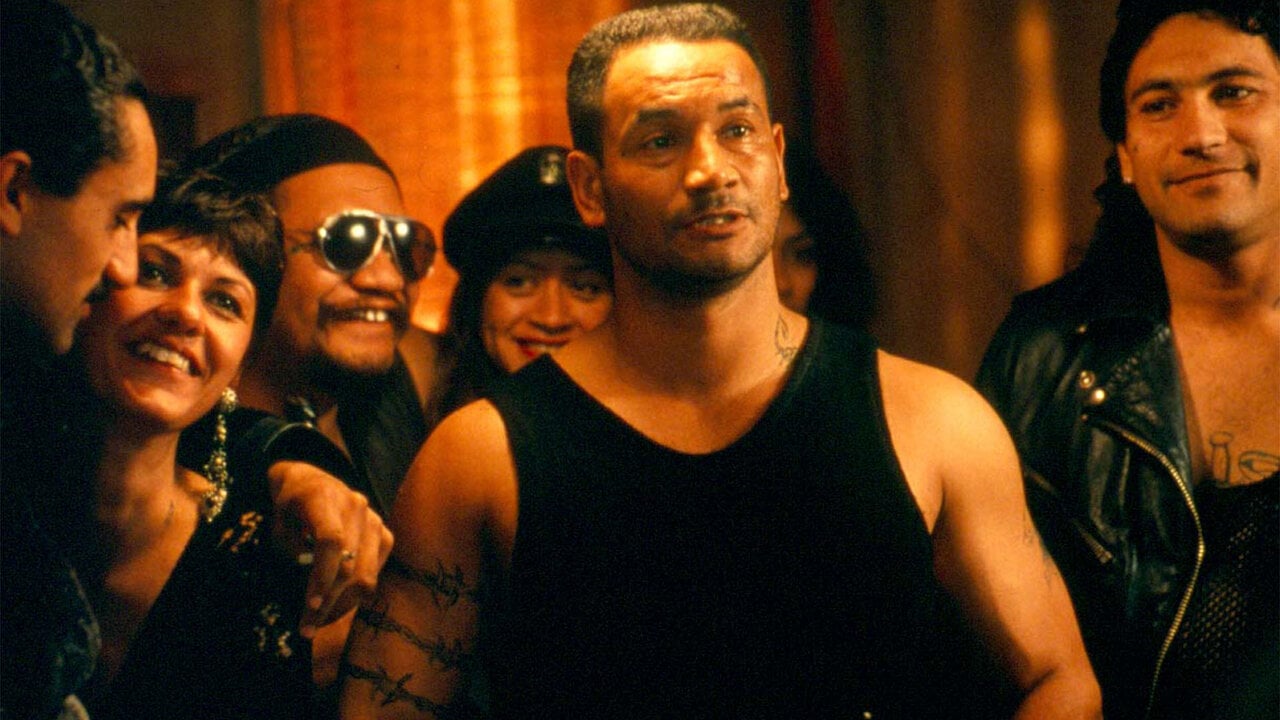

Lee takes this premise to much more interesting places than sports movies usually go. The plot is a melodrama of sorts, in which Jesus’ incarcerated father Jake (a top-tier Denzel Washington) must convince his son to declare for the governor’s alma mater in exchange for a reduced sentence. The pair are estranged — Jake is in prison for the death of Jesus’ mother — making this as much a tense examination of family and forgiveness as it is a sports movie. And what a sports movie it is: Lee makes his love of basketball not just abundantly clear but also infectious, opening the film on soaring, balletic images of the sport that suggest it’s no mere game, but something unifying, artistic, and ultimately salvatory.

What stands out

That sense of basketball being “poetry in motion” is underscored by He Got Game’s extremely liberal use of music: it’d be quicker to count the scenes that aren’t set to Aaron Copland’s orchestral compositions or Public Enemy’s original songs than the ones that are. Far from being a distraction, though, the constant presence of Copland’s grandiose strains and the incisive lyricism of Public Enemy only add to the epic atmosphere of the film and sharpen its critical view of the capitalist feeding frenzy that the young Jesus, poised on the edge of success, finds himself at the center of.

Comments

Your comment

UP NEXT

UP NEXT

UP NEXT

Curated by humans, not algorithms.

© 2025 agoodmovietowatch, all rights reserved.