50 Best Foreign Movies on Netflix Right Now

“Once you overcome the one-inch tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films,” Parasite director Bong Joon-ho is now famous for saying.

To celebrate that sentiment, here are our curated recommendations for the best non-English-language movies streaming on Netflix. Like all lists on agoodmovietowatch, this one is updated every month to remove expiring movies and add new ones, so make sure you bookmark it!

Happy watching.

An all-female action comedy that doesn’t get self-serious about the way it’s subverting the genre — Wingwomen feels like a breath of fresh air. It wisely grasps that plot isn’t paramount for a movie like this, and so it joyously dunks on cerebral scenarios with its unabashedly silly story convolutions, like when its professional thieves take a brief pause from their momentous One Last Job™️ to sail to Italy and exact bloody, flamenco-delivered revenge on the gangsters who killed their beloved rabbit. Exotic Mediterranean location-hopping isn’t the only way Wingwomen milks Netflix’s finance department for all it can get, either: director-star Mélanie Laurent also packs in all manner of stunts, from spectacular base-jumping sequences to dramatic drone shootouts.

For all its breezy style, though, there is real heart here, and not the kind that feels crafted by an algorithm. It’s true that a late twist unwisely uses the movie’s embrace of implausibility for emotional ends, but otherwise, the relationship between its professional thieves — ostensibly platonic but very much coded otherwise (a la Bend It Like Beckham) — has surprisingly sincere warmth. Thanks to the cast’s natural chemistry and characters that feel human despite the ridiculous plot, Wingwomen is much more moving than you might believe possible for a Netflix action-comedy.

Full of charm and nostalgia, Bang Woo-ri’s first feature film is a love letter to the late 90s—and to the heartstopping experience of first love, as high school student Na Bo-ra tries to get to know her friend’s crush Baek Hyun-jin. While at times immature, she comes across as endearing through Kim Yoo-jung’s charismatic, devoted performance. And as Na Bo-ra goes through all the ways people wooed each other in the 90s—figuring out each other’s phone numbers, filming each other through old camcorders, renting out VHS tapes—the film evokes memories of our own first loves. Even with some underdeveloped characters and certain contrived moments, 20th Century Girl is still a stunning picture of young love at the turn of the century.

In the years since Fan Girl’s original release in the Philippines, its ultimate message and execution has become polarizing: is it enough that the film shows the corruption of a parasocial relationship into an abusive one, without offering much hope? Is its vision of justice actually constructive or disappointingly limited? No matter where you fall, it’s exciting that a movie can stir up these kinds of questions through a bizarre dynamic between characters, in a place that’s clearly set somewhere between reality and delusion. The narrative is circular and frustrating for a reason—a constant push and pull as the titular fan girl keeps getting drawn back into the celebrity’s orbit—and the film only grows more disturbing with each repetition.

After the La Manada rape case in 2016, it was necessary to document this event, especially since the widespread national outrage and demonstrations managed to move the country to change the way Spain defines consent. You Are Not Alone: Fighting the Wolf Pack documents this arduous journey. While it’s done through the familiar Netflix true crime approach, there’s some respect given to the victim that hasn’t been given previously by the media. The film sticks to the actual verbatim words used by the victim, albeit edited for clarity, but they ensured that their words were not accompanied with photos or similar looking actors, keeping the truth of their words without risking their safety. While the documentary’s direction isn’t new, the outrage is still felt, as well as the genuine hope of a country that came together to ensure justice.

Despite being colorful and full of music like many Bollywood films, there’s a noirish sensibility to Talaash that makes it stand out. The plot takes on a familiar investigation. The protagonist, portrayed by Aamir Khan, is broody and jaded due to grief. And of course, there’s a femme fatale portrayed by Kareena Kapoor Khan, who remains frustratingly yet compellingly elusive. All this together creates an incredibly suspenseful atmosphere, so the twist at the end might prove to be divisive to viewers. To this viewer, however, it was a clever way to tie in Surjan’s grief into the story. Talaash is terrific.

Dear Ex is a family drama that explores LGBT+ issues in contemporary Taiwan. As much as it is a movie about how people cope with loss, it’s a powerful, heartwarming, and intimate portrait of the relationship between Jay and Song Zhengyuan and all the obstacles they face.

While the themes of Dear Ex are heavy, the director makes the viewing experience easier for the audience thanks to humorous and witty dialogue. Meanwhile, the history between Jay and Song Zhengyuan’s relationship unfolds in a very beautiful, almost poetic way, and by the end of the movie, we understand that everyone gets their own kind of forgiveness. The way the characters effortlessly show that love is something beyond genders is admirable, and it is great to see how everyone gets their own kind of forgiveness whether it’s from themselves or from others by the end of the movie.

Friday Night Plan resembles many a classic teen film (most notably, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and Booksmart), but it also doubles as a thoughtful inquiry into the delicate bond between siblings who could not be more different from one another. Sid and his younger brother Adi (Amrith Jayan) have different ideas of what matters most in life, ideas that get tested when their mother’s car gets towed away during their night of fun. Sid thinks it’s only right to come clean and retrieve the car no matter what, but Adi believes this can all wait until tomorrow morning: tonight is Sid’s night to celebrate and finally connect with peers he’s shut off all his life. This tension comes as a surprise in what otherwise looks like an ordinary teen movie, but it’s also a welcome addition that helps Friday Night Plan stand out from the rest.

At the fringes of society, sometimes, all you have is your family. You would do all you can to feed, clothe, and protect them, and your fate hangs in the balance of what they do in return. Abang Adik is centered on two undocumented orphans in Malaysia, and because they only have each other, Abang does all he can legally and within his capabilities as a disabled man to scrounge up some money, but Adik tries to gain more secretly, resorting to scamming fellow illegal immigrants. Writer-director Jin Ong portrays their plight realistically, but more importantly, the drama works because Ong prioritizes crafting the compelling dynamic between them, making it much more heartbreaking when the loss of their one chance changes everything. Abang Adik may not be a perfect drama, but it’s a daring debut that’s needed.

This is a gorgeous Danish period drama that’s based on a famous story and book in Denmark called Lykke-Per (or Lucky Per) by Nobel Prize-winning author Henrik Pontoppidan.

Per, the son of an overbearing catholic priest, leaves his family house in the country side to seek a new life in Copenhagen. His passion about engineering was at the time contrary with the Christian faith, but manages to introduce him to the capital’s elite, and a chance at social ascension.

Lykke-Per and A Fortunate Man are about nature versus nurture. Per’s passion about engineering and renewable energy (back in the 1920s) is set against his need to emancipate and the pride that was instilled in him by his upbringing.

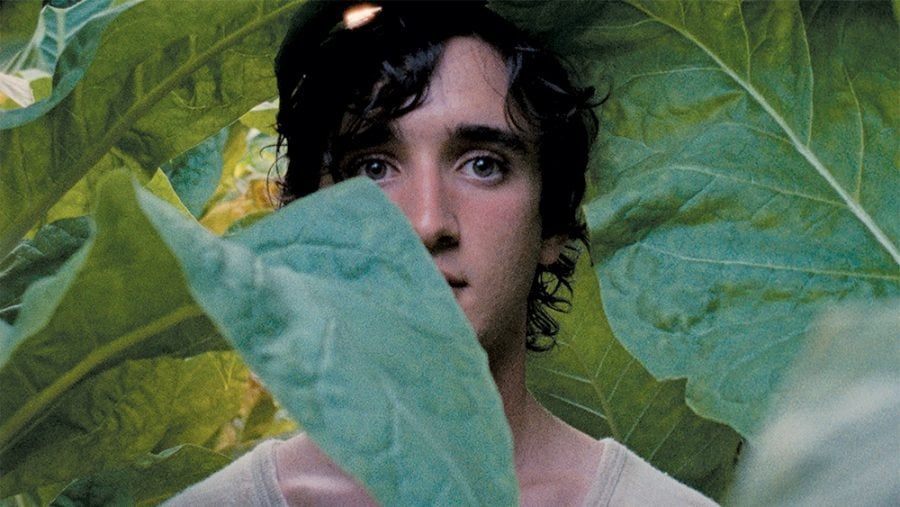

Set in 1970s Italian countryside, this is a quirky movie that’s full of plot twists.

Lazzaro is a dedicated worker at a tobacco estate. His village has been indebted to a marquise and like everyone else, he works without a wage and in arduous conditions.

Lazzaro strikes a friendship with the son of the marquise, who, in an act of rebellion against his mother, decides to fake his own kidnapping. The two form an unlikely friendship in a story that mixes magical realism with social commentary.

The Platform is the closest thing to Parasite released so far. This interesting Spanish movie is about 90% a science-fiction drama and 10% a horror movie. It’s an allegory set in a future where prisoners live in vertical cells, and each cell has to wait for the cell above it to eat to get food. Depending on the floor where prisoners wake up, they might not get any food at all. This creates for disturbing situations that are hard to see as not representative of our modern societies.

Remember the creepy blind nun from the Spanish horror film Veronica? While many nun-related horror films have nuns as its horror element, this time it’s the nun that gets spooked in Sister Death. The new release expands on her backstory, taking the story back in history, in her start as a novitiate in the former convent, a location that’s been changed after the terrors inflicted towards the nuns during the Spanish Civil War. While the film doesn’t delve that deeply, focusing instead on the slowly building up the film’s terror, there is something here about the hidden violence and covered-up trauma that still haunt the Catholic church in Spain, especially to those that have taken vows. Director Paco Plaza meticulously frames each terrific sequence with the isolating doubt in one’s faith that Narcisa experiences.

Gangster films have an issue of glorifying organized crime, and in some ways The Pig, The Snake, and The Pigeon does the same. There are excellent, action-packed fight scenes that makes Ethan Juan as Chen Kui-lin look so damn cool, and the journey Chen takes as a stern criminal out for his legacy definitely romanticizes the character, but it’s so compelling to see him contemplate the purpose of his life through confronting those like him, who tend to move for the ideas of love and spiritual detachment. There are some moments when the pacing falters, but The Pig, The Snake, and the Pigeon delivers on its ending and reimagines the gangster as something to remember.

2023 was a great year for animation with films like Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, Nimona, and The Boy and the Heron, but there was another animated gem that flew under the radar and that’s jazz drama Blue Giant. It’s a pleasure to both the eyes and the ears as Dai Miyamoto blows on his saxophone, adding Hiromi Uehara’s incredible soundtrack and Yūichi Takahashi’s dynamic animation to the high contrast manga visuals, and the way the story unfolds the different avenues of pure passion these three have for jazz is absolutely captivating. Blue Giant is just so well-done that it’s no surprise it garnered a bigger-budgeted encore eight months after its premiere.

At first glance, Dil Chahta Hai is an ordinary ensemble romcom. There’s some guys, there’s some girls, and they fall in love in their own special way as befitting the general archetype of protagonists we’ve seen in other romcoms. But to the film’s credit, it’s made pretty well. Many viewers can appreciate the catchy songs, the charismatic leads, and the spectacular way writer-director Farhan Akhtar stages each number, but what makes his debut work is how in tune it was with modern Indian youth, and the way it grounds all three love stories through the friendship of three young men fresh out of college. Dil Chahta Hai balances its romantic drama with the support of friends, similar to how relationships work in real life.

In the Dead Talents Society, ghosts haunting humans are less of a scare, and more a performance that can grant fame and fortune in the underworld. It makes for incredibly charming comedy. It affectionately satirizes East Asian horror in such a fresh way, comparing a ghost being remembered to today’s social media influencers, with views and validation directly tied to survival. However, as these ghosts scramble to scare unwitting humans, writer-director John Hsu resolves their need to be seen through the familiar path of fun and friendship, an approach that works with its offbeat humor and incredible performances. Dead Talents Society is very goofy, but it’s a unique horror comedy that won’t easily be forgotten.

5 Centimeters per Second is a quiet, beautiful anime about the life of a boy called Takaki, told in three acts over the span of seventeen years. The movie explores the experience and thrill of having a first love, as well as being someone else’s. In depicting how delicate it is to hold special feelings towards another, director Makoto Shinkai also perfectly captures how cruel the passing of time can be for someone in love. While the early stage of the movie maintains a dreamy mood, as the stories develop we become thrust back into reality, where it is not quite possible to own that which we want the most. All things considered, 5 Centimeters per Second is a story about cherishing others, accepting reality, and letting people go.

This sensitive and elegantly crafted melodrama recognizes that a death in the family doesn’t have to lead to the same expressions of mourning we expect from movies; there might not be any real sadness at all. But when different family members come together again and bring their own personal conflicts with them, suddenly everyone else’s little griefs fill the space, and the road to recovery becomes even messier. Little Big Women understands all this with an understated touch and brilliant, naturalistic performances from its cast. It makes for a loving tribute to the generations of tough and complicated women who often hold a family together.

When your dad is single, and he isn’t in a relationship with someone else, naturally, a kid would wonder about their real biological mother. Hi Nanna is a take on this familiar tale, though Shouryuv’s directorial debut makes it feel brand new by telling the love story in a way a father would tell his daughter– mindful of the audience, so slightly embellished, but no less sweet. By doing so, it makes the viewers yearn for the lost love before raising our hopes and revealing the possibility of getting it back, especially with the natural chemistry of Nani and the striking Mrunal Thakur.

Unlike plenty of time torn films, Maboroshi is the kind of film that doesn’t have a straightforward explanation for the town of Mifuse standing still in time. But even when it doesn’t have a logical reason, the way the film unfolds has a distinct feeling as it explores the illusions the town either could cling to, or release to grow. This kind of storytelling would be familiar to fans of the prolific screenwriter Mari Okada, who just started directing in 2018 with Maquia: When the Promised Flower Blooms, but even those new to her work would appreciate the pure emotion driving Maboroshi, if they can let go of reality and enjoy MAPPA’s exquisite art for a moment.

After Loving Vincent, DK and Hugh Welchman’s iconic oil paint animation initially seems like old hat, but this time the style is actually more fitting for their second feature. As an adaptation of the iconic Polish novel, The Peasants had to live up to the book’s reputation as the Nobel-winning depiction of the Polish countryside, one of the first to take an intimate look into the lives of the commonfolk, their customs, beliefs, and traditions. The Welchmans’ naturalist, impressionist art style lines up with the way the original Chłopi was inspired by these movements, as does L.U.C’s selection of mesmerizing, haunting Polish folk songs. While the plot is a tad cliché, it only does so in the way folklore tends to weave the same threads. It just so happens that the threads in The Peasants lead to violent ends.

Prayers for the Stolen takes more time to observe life in its rural town, than to showcase the action and violence inflicted by the cartels that pass by. It’s a needed perspective. This move drives home how long these cartels were left unaddressed, as the women of the town have gotten used to the danger and were unable to leave for whole generations. It makes clear how their lives have been interrupted, limited, and held hostage at the whims of whichever group takes over the village. But it also allows writer-director Tatiana Huezo to help us witness the love and tenderness Ana holds for her mom and friends. Prayers for the Stolen is tough to watch because of the safety they lack, but it’s also a beautiful tribute to the relationships they’ve forged despite that.

COVID-19 raised concerns about sanitation and cleanliness, but in a society that just banned discrimination against “impure” castes seventy years ago, these concerns feel reminiscent of previous caste prejudice. Writer-director Anubhav Sinha presents this social inequity through Bheed, a black-and-white drama set in a fictional checkpoint as the lockdown restricted travel between different Indian states. As the people in the checkpoint wait for the updated government regulations, tensions rise between the officers and the travelers, as the stuck migrants worry about hunger, thirst, and infection. While it’s definitely a heavy film to watch, this film doesn’t exploit the pandemic as fodder for drama. Instead, Bheed realistically portrays how a crisis like COVID-19 exacerbates existing social inequity.

After two adaptations, with the 1982 version considered a Christmastime classic for Polish families, Forgotten Love can seem like a redundant take on the iconic Polish novel. With twenty more minutes, it seems like the new Netflix adaptation could only improve its take through better production design, and sure, it certainly delivers that pre-war aesthetic through period-accurate costumes, props, and sets. However, Forgotten Love takes a more streamlined approach to the novel’s plot, through changing certain character choices. Without spoiling too much, some choices paint certain characters in a better light, while other changes prove to add an entertaining twist, such as the humorous way the villagers defend Kosiba. Znachor takes the 1937 story into the present, bringing a new generation through the emotional journey of the cherished Polish tale.

Inspired by the Spiniak case, Blanquita reimagines the infamous scandal through mirrored interrogations and disorienting viewpoints. Blanquita rewrites the original witness, whose fictional variant, in turn, rewrites the abuse faced by victims as her own. She is transformed from a clueless liar, into someone still a liar, but one that did so when every other possible witness has been discarded for being unreliable, for being too traumatized to go through the judicial process unflinchingly. The film takes on a provocative subject matter, at a time when real life sexual abuse allegations are treated with the same scrutiny Blanca faces. However, Blanquita does so in a way that gives its complexities the weight it deserves. It’s a fascinating thriller, a quandary that tests the idea of ends justifying the means… But it’s one that’s disturbing, given the consequences to each crime.

Given a budget from Netflix to make a documentary on Korean film, some would have chosen instead to make one for big Korean filmmaking personalities like Academy Award winner Bong Joon-ho, who is featured here. However, director Lee Hyuk-rae instead creates Yellow Door, a love letter to the ‘90s film club that inspired a generation. The warm way each member tries to remember the club made decades ago, and the handy, almost cheeky, animations makes it feel like we’re there in the club with them, just listening to friends reminisce about the way they obsessed about film, even if it wasn’t the major they were studying in. It’s so nostalgic and sentimental, and in shifting its focus, it celebrates the lovely experience of finding a community of like-minded people that’s just obsessed with film as you are.

The fantasy of being able to have the body you once had is impossible in real life, but we can watch it play out in fiction. While previous depictions of this idea rightfully point out ageism and how much worse people treat the old, Miss Granny also celebrates the wisdom and experience that could only come from the years Oh Mal-soon has gone through, through an engaging script and the quirky performance of Shim Eun-kyung. It’s so funny seeing people taken aback, surprised, and astounded by old Oh Mal-soon in her young body, but what makes it work is the way director Hwang Dong-hyuk introduces her to us bit by bit, crafting a character that at first glance seemed to be a rude and controlling grandma, but is actually a woman that didn’t get to enjoy her youth due to the sacrifices she made for her loved ones. Miss Granny makes the case that there are timeless things that we can return to and appreciate, but there are also things that we’re willing to let go of our youth for.

What makes people attempt to climb the tallest mountain in the world? Many might be motivated simply for the title, but in this animated adaptation, it’s the obsession that gets them going. The Summit of the Gods starts its journey with the real life mystery of George Mallory’s 1924 Everest climb, which, if answered, could reshape the history of mountaineering as we know it. So, of course, a reporter like Makoto Fukamachi has to follow the story. As we witness his investigation, and get to know the climber that might have all the answers, Habu Joji, it’s easy to get sucked into their story with the breathtaking visuals, the atmospheric soundscape, and the characters that we get to know on a personal level. The Summit of the Gods understands why they do what they do, despite each step pulling them further away from safety.

Horror movies have always been creepier to me when they play on our fear of the “unknown” rather than gore. Under The Shadow does exactly that. The story is based around the relationship of a woman, Shideh, and her daughter, Dorsa, under the backdrop of the Iran-Iraq war. As widespread bombings shake the ground beneath their feet, the two grapple with a more insidious evil that is faceless and traceless, coming and going only with the wind. The movie’s dread-effect plays strongly on feelings of isolation and helplessness. The scares are slow and it’s obvious the director takes great care in making every single second count and in raising the unpredictableness of the action. Like the bombs, the audience never knows when or how the next apparition will materialize. The former is always on the edge of fear, wondering what is no doubt there, but is yet to be shown on the frame. In terms of significance, Under The Shadow features too many symbolisms to count and will most likely resonate with each person differently. But one thing remains relatively unarguable: this is a wonderful movie.

In the Mexican film A Cop Movie, director Alonso Ruizpalacios mixes fact and fiction, documentary and narrative, to tell the tale of Teresa and Montoya, two police officers whose dreams are dashed by the corruption of their trade and who, eventually, find love and comfort in each other.

Ruizpalacios takes thrilling risks in structuring this genre-bending story—cutting stories into parts, jumping back and forth between the harrowingly real and captivatingly non-real. For all the experimental maneuvers he makes, however, the through-line is always Teresa and Montoya: particularly, their love for each other and for an institution that should have, in an ideal world, supported them and the people they vowed to protect.

To its credit, instead of merely humanizing the controversial police force, A Cop Movie adds some much-needed nuance to the big picture. At the end of the day, they’re no different than any other underpaid laborers working desperately to make end meets. A Cop Movie doesn’t gloss over the fact that the police, like so many other workers, are stuck in a rotten system that’s long overdue for a major overhauling.

After years of documentaries covering Thailand’s controversial issues, some of which have been temporarily banned by the Ministry of Culture, Nontawat Numbenchapol takes a step into feature film in Doi Boy. The plot covers plenty of the topics he’s previously depicted– immigration, prostitution, and corruption– but it unfolds naturally into a slow-paced, but moving drama where an undocumented sex worker tries to find home. Awat Ratanapintha as Sorn excellently leads this journey, but Arak Amornsupasiri as reluctant cop Ji, and Bhumibhat Thavornsiri as passionate activist Wuth also make their mark. While the film doesn’t delve into the intricate intersectionality, it feels like that’s part of the point. The notion of a nation doesn’t care about people’s dreams, even if that dream is for the nation to be better.

Given the title, it isn’t surprising that Falling in Love Like in Movies would be a metanarrative with the main romance mirroring the filmmaking and the filmmaking reflecting the main romance. It’s a familiar approach, and at first, Falling seems to follow the inevitable ending where the couple falls in love, but right on time, in around Sequence Four, writer-director Yandy Laurens chooses a more honest, less chosen path– a path that plenty of previous romance films hasn’t examined– that still falls within the eight sequence screenplay structure Bagus talks about. While Bagus is pitching his film to Hana, and to his producer, Jatuh Cinta Seperti di Film-Film pitches a new way of thinking about love, grief, and of course, filmmaking.

Grandparents are often depicted as innately loving, especially towards their grandchildren, so it’s a delight to see someone like M’s Amah, who is testy and tenacious, and quite proud to be doing her own thing even in her old age. She runs her house alone and sells congee in her neighborhood, and even when presented with the worst possible news, she refuses pity, only allowing M back in her life after he proves his motives are sincere. M, to his credit, is believably selfish and sensitive as a young school dropout. Together, the two and their crackling push-and-pull chemistry are a blast to watch. It’s tender, but never overly saccharine, and no matter how much you resist you’re sure to shed a few tears. How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies may not have the most original plot (I’m sure you’ll be able to guess the ending just by reading the premise alone), but it’s thoroughly engaging, not only because of the two leads, but because of it’s relatable messages about family dynamics (especially Asian family dynamics), money, and legacy. The gentle, unobtrusive cinematography by Boonyanuch Kraithong makes it extra easy on the eyes too. I only wish the movie explored the misogyny of tradition more, instead of merely touching upon it (“Sons get the goods, daughters only get the genes” is such a brilliant line), but I suppose that would need a female writer/director at the helm.

While based on the Mononoke series, which is in turn, a spin-off of Ayakashi: Samurai Horror Tales, it might seem that Mononoke The Movie: The Phantom in the Rain would require some background reading for people new to the story. Thankfully, there’s no need to do homework for this beautifully designed masterpiece, as the Medicine Seller takes on a new case with every installment. 2024’s Phantom in the Rain (also known as Paper Umbrella) unfolds its world with ease, with doors opening and closing to a select few for a high-pressure, hierarchical imperial household. Immediately, the visuals are stunning, with traditional ukiyo ink and paper mixed with modern kaleidoscopic fill and movement, but even without the gorgeous art, the first Mononoke movie works with its eerie horror, intense sound design, and a compelling mystery driven by court intrigue and vengeful spirits.

You don’t need to be familiar with the rest of the Rurouni Kenshin live-action movie series—or the original manga and anime, for that matter—to appreciate The Beginning as a powerful period drama in its own right. This is a story that courses its historical context about a tumultuous time in Japan’s past through a stoic, fearsome protagonist who can’t seem to escape the violence that’s become his only function. And even more impressively, as a prequel, the film keeps a heavy sense of dread about it, even if you’re sure about which characters are meant to survive in order to appear in the previous films. It’s the mark of any great tragedy that even the things that are destined can still feel so painful.

When a man languishes in a prison of an enemy country for more than two decades, anyone would wonder what happened. The worst easily comes to mind. Despite Indian-Pakistan relations then, Veer-Zaara surprises us instead with a love story. It’s a rousing romance up to the standard filmmaker Yash Chopra has set, with the soaring melodies, the colorful shots, and the emotional performances from Shah Rukh Khan and Preity Zinta. However, it stands out from Chopra’s oeuvre because of the way it celebrates his birthplace of Punjab, the province that was split between India and Pakistan in his teenage years. Rather than pitting both nations against each other, Veer-Zaara instead celebrates the culture shared on both sides of the border.

A zombie virus breaks out and catches up with a father as he is taking his daughter from Seoul to Busan, South Korea’s second-largest city. Watch them trying to survive to reach their destination, a purported safe zone.

The acting is spot-on; the set pieces are particularly well choreographed. You’ll care about the characters. You’ll feel for the father as he struggles to keep his humanity in the bleakest of scenarios.

It’s a refreshingly thrilling disaster movie, a perfect specimen of the genre.

The Hand of God is the autobiographical movie from Paolo Sarrantino, the director of the 2013 masterpiece The Great Beauty. He recently also directed The Young Pope with Jude Law and Youth Paul Dano, both in English. He is back to his home Italy with this one.

More precisely, he’s in his hometown Naples, in the 1980s, where awkward teenager Fabietto Schisa’s life is about to change: his city’s soccer team Napoli is buying the biggest footballer at the time, Diego Maradona.

Sarrantino, who is also from Naples, made this movie that is half a tribute to the city and half to what it meant growing up around the legend of Maradona.

The Hand of God is to Sarrantino what Roma was to Alfonso Cuarón, except it’s more vulgar, fun, and excessive. It is equally as personal though, and it goes from comedy to tragedy and back with unmatched ease.

The Kings of the World is a surreal coming-of-age movie that follows Rá, Culebro, Sere, Winny, and Nano, street kids who are on their way to claim land that’s rightfully theirs. Their one goal is to finally make a home after living without one for so long, but they’re hindered by the inevitable tragedies that befall kids of their kind: impoverished, alone, and abandoned.

The title is ironic, but it also hints at their state of mind: these boys are unstoppable, rabble-rousers who live like there’s no tomorrow. They tear down private property and invade inns not out of spite, necessarily, but out of a knowledge that whatever they do they’re gonna be put down anyway, so they might as well live without rules.

Tackling powerful themes like land restitution and youth neglect, The Kings of the World is one of the most agonizing movies you’ll ever see. It’s also Colombia’s official Best Foreign Language Film entry in the 2022 Academy Awards.

Love can happen anytime and anywhere, but some of the best love stories are about the kind of love that fundamentally challenges the lovers in question, as well as the kind of people these lovers are. One such film that does that is Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge. It’s a simple holiday romance, but the straightforward plot works because of the leads’ playful chemistry and because of the way writer-director Aditya Chopra understands the characters of his directorial debut. While abroad, the two young adults are pushed to think about each other as they navigate an unfamiliar continent, but as they return to their regular lives– with Raj still remaining in Europe and Simran moving back to India– they’re challenged like many second-generation kids, to either return to the culture they grew up in, or adapt to the culture of where they’re going. Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge suggests that being Indian and living abroad, as well as personal happiness and respecting one’s family, doesn’t have to contradict, and it’s these ideas that makes it a classic.

It’s been acclaimed as one the best Kung Fu movies ever made. You are probably wondering why this contemporary movie made that short list when its genre had its peak decades ago: it is visually striking and at the same time surprisingly story-oriented. As you would expect of course, there is quite a fair amount of action scenes, but the characters are also brilliant which is very uncommon in this type of movie. It is an exciting movie, and worthy of any compliment or good rating it may get.

Two storylines take place in this Parisian animation: one of a Moroccan immigrant who works as a pizza delivery guy, and the other of his hand, somehow no longer part of his body, but also going on a trip around Paris.

The hand storyline is not gory by the way, except for one or two very quick scenes. Mostly, this is a film about loneliness and not being able to find your way back, both as an immigrant who misses how they were raised and as a hand who misses its body.

Sporting some of the most beautiful animation work this year, this movie premiered at Cannes where it became the first-ever animated film (and Netflix film) to win the Nespresso Grand Prize.

Mars One is a tender, wholesome drama that centers on The Martins, a family of four living on the fringes of a major Brazilian city. Their lower-middle-class status puts them in an odd position—they’re settled enough to have big dreams and occasionally lead lavish lives (the mother and the daughter like to party) but they barely have the means to pursue that kind of lifestyle. As a result, they’re always searching and wanting, aiming high but almost always falling flat on the ground.

There is no actual plot in Mars One. Instead, it studies its characters in a leisurely and almost offhand manner. The approach is so naturalistic, you’ll almost forget you’re watching a movie. But it’s still gorgeously shot and staged, Brazil being an inevitably striking background. At once gentle and vibrant, this big-hearted film is a must for those who are suckers for well-made family dramas.

When two young brides are mistakenly swapped on a train, it’s a difficult situation, much more so when the brides in question are both veiled and wearing the same red bridal attire. This seemingly simple swap is the entire plot of Laapataa Ladies, but director Kiran Rao transforms this mishap into a hilarious, yet realistic, satire that challenges plenty of the norms enforced on women in the country. As Phool and Jaya switch places, the film understands where their respective mindsets come from– Phool having not learned much about the world, and Jaya having been jaded by it– but the film doesn’t stop there. It brings them to places that challenge those mindsets, and in turn, they challenge the people around them too, by actively making choices from the mindsets they had to hold to survive. Laapataa Ladies is what it says on the tin– Laapataa is the word for lost– but the sharply written characters, the witty dialogue, and the subtle social commentary make this charming love story one of a kind.

A gritty and realistic thriller set in France’s notorious capital city of crime – Marseille.

Zachary is released from Juvenile prison to learn that his mother has abandoned him. He finds kinship in an underage sex worker by the name of Shéhérazade.

This seems like the set-up for a tough watch, but Shéhérazade plays like a romance when it’s slow, and a crime thriller when it’s fast (it’s mostly fast). Everything about the story and two leads’ relationship rings true. Added to the fact that it has no interest in emotionally manipulating you, the movie is more gripping and thought-provoking than sad.

A great story, fantastic acting from the cast of first-timers, and outstanding direction give the feeling that Shéhérazade is bound to become a modern classic. If you liked City of God, you will love this.

In The Sun, a family of four is dealt with tragedy after tragedy, beginning with the younger sun A-ho’s sudden incarceration. The mother is sympathetic but the father all but shuns him as he chooses to throw all his affection to A-hao, the older brother, and his med school pursuits instead. Themes of crime, punishment, family, and redemption are then explored in gorgeous frames and mesmerizing colors with director Chung Mong-hong doubling as the film’s cinematographer.

Despite itself, The Sun never falls into cliche melodrama territory. Its heavy themes are undercut by naturalistic acting and poetic shots, resulting in a deeply emotional but balanced film. Rich in meaning and beauty, The Sun will surely stay with you long after your first watch.

Perhaps the most depressing but vital movie produced by animation giant Studio Ghibli, Grave of the Fireflies is a searing and sweeping drama that covers the horrors of World War II through the eyes of teenager Seita and his young sister Setsuko. Between the violence of war and the tragedy of loss, the siblings struggle to preserve not just their lives but their humanity. In typical Ghibli fashion, there are moments of gentle beauty to be found, but instead of conflicting with the overall stark tone of the film, they successfully underscore war’s futility and brutality, making Grave of the Fireflies one of the most important anti-war narratives ever told.

Real life tragedies, especially one that’s as sensationalized as the Miracle in the Andes, can be tough to depict on screen. On one hand, the film has to keep true to the story but also maintain some form of spectacle to keep people watching. Past depictions of the 1972 crash are preoccupied with the cannibalism portrayed by big name actors, but Society of the Snow takes a different route. The actors are newcomers, the threats to their lives don’t require daring action stunts, and the cannibalism is limited to small chunks indistinguishable from animal meat. Instead, the spectacle of Society of the Snow is the human spirit– the vulnerability, the respect, and the generosity they’ve given each other in order to survive. It’s still an uncomfortable watch, especially since we get to know some of the survivors before the crash, but it’s definitely a transcendent addition to the genre dedicated to the miracle of existence.

Winner of a Camera d’Or, the debutant’s prize at the Cannes Film Festival, Director Houda Benyamina’s first feature film is fast-paced and full of energy. Deep in the impoverished suburbs of Paris, the infamous banlieues, it tells the story of Dounia (played by Oulaya Amamra), a mouthy teenager who is not content with what society is prepared to hand out to her. She’s angry; she wants more. And so, together with her best friend Maimouna (Déborah Lukumuena), she decides to finally make some cash as a runner for a drug dealer. While there’s obviously some feminism in there somewhere, that’s not at the heart of what this film is about. It’s about the economic reality in a world of poverty and about two friends and their desire for freedom—no matter what the cost. An exhilarating and thought-provoking debut helped along by Amamra’s amazing acting.

Abuse is bad and should be reported, full stop. But it’s not so easy to do so, when abusers stay in positions of power, and the people who are assigned to keep them in check are cowardly against them. Silenced depicts true crime novel The Crucible, which in turn, is based on a real life case of the Gwangju Inhwa School. Through the perspective of a new art teacher, Silenced systematically outlines how difficult it is to deliver justice, from the way the school administration bribed police and the education department, to the way the court didn’t even think to hire a deaf interpreter. It’s a horrific watch, but the intensity of the depiction was needed, given that this film’s release pushed South Korea’s government to change their laws and the actual school shut down within the same year.